Klipa log week 5 יומן קליפה שבוע

Text in Hebrew and English & one Image טקסט ודימוי אחד

העצים של ברגן-בלזן

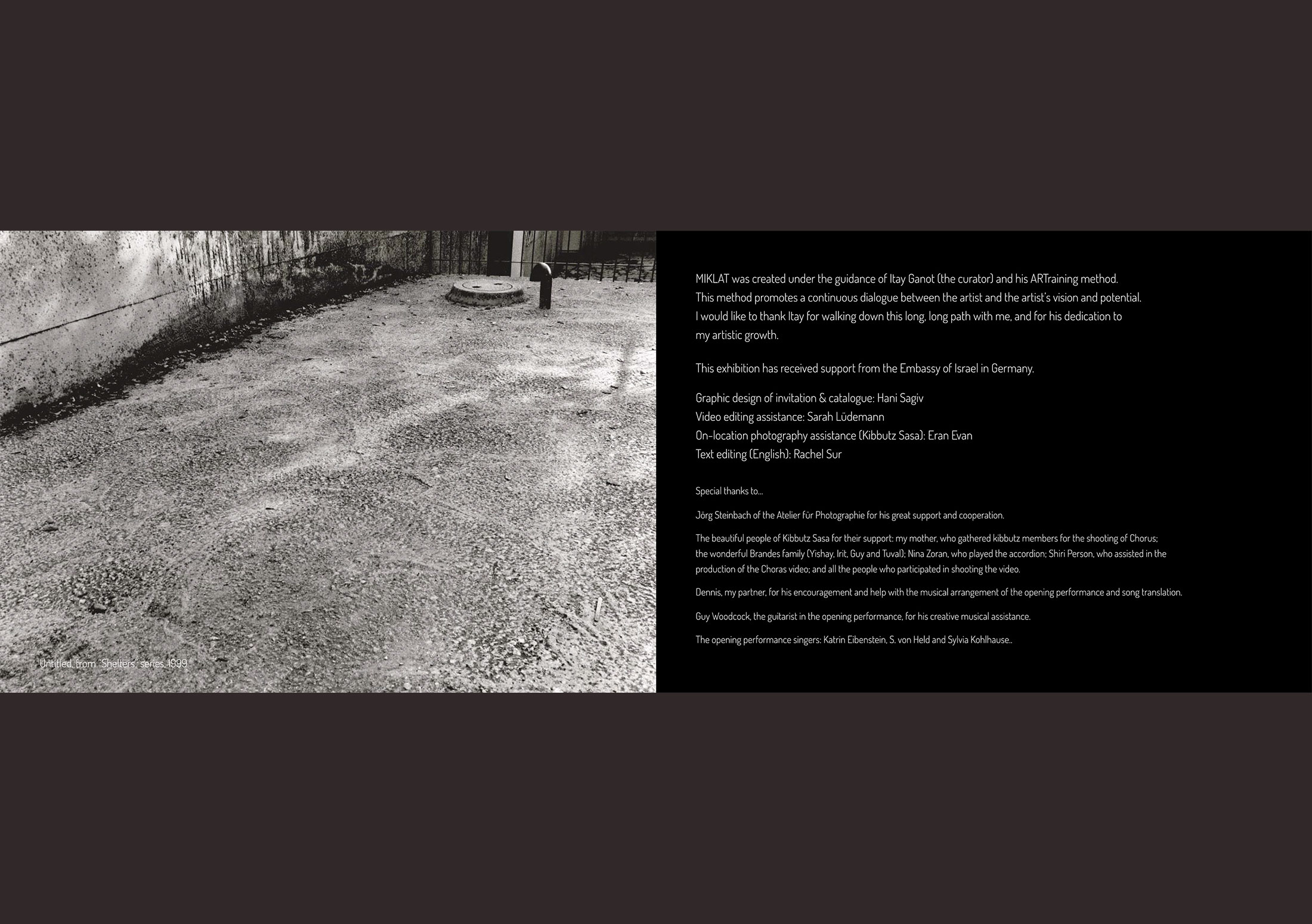

כשנסענו לשם עצרנו לפיקניק בוקר והוצאנו את הסנדוויצ’ים שהכנתי, וביצים קשות שרוזה הכינה. ישבנו על ספסל עץ גדול בנוף כפרי עם בתים אדומים ומסביב שמענו מכונות יריה בצרורות. מסתבר שנסענו בכביש צדדי שהוא שטח אימונים גדול של הצבא הגרמני. משם עד למחנה היו שלטים שהזהירו לא לעצור בצדי הדרך ושהצילום אסור

מאז שהגעתי לגרמניה לפני שמונה שנים היו לא מעט רגעים שהעבר של המקום בא לפגוש אותי, בלי להתאמץ ובלי להתכוון. מזכיר לי מה המקום הזה שבו בחרתי לחיות, ומה המשקל שהוא נושא עימו.

לא באתי לפה רדוף בסיפורי סבים על השואה. אל החור השחור בהיסטוריה המשפחתית שנקרא “החיים של סבא שמחה לפני”, לא צללתי מעולם למרות שאני שנים רוצה, מאוד רוצה לדעת ולהעלות שם צבע. ברזידנסי בברלין עשיתי תמונות בהשראת תמונה שלו במדי הצבא הסובייטי, והתמונה מהפספורט שלו משמשת אותי עד היום בעבודות. הוא מת כשהיתי ילד והינו בארצות הברית, כמה שנים אחר כך מת אבא שלי שכנראה לא ידע מעולם הרבה יותר, כי סבא שמחה לא דיבר ולא סיפר. הילדים בקיבוץ זוכרים אותו כסבא החביב שמגיע ומחלק סוכריות. באחד הביקורים האחרונים בארץ הגעתי עם דניס לבית התפוצות לחפש במאגר מידע, לא העליתי דבר

אחד מהמפגשים האלה עם העבר, היה שיעור עברית ראשון עם כריסטינה, במאית גרמניה בדירה היפה שלה בפרנצלאואר ברג, מהר מאוד היא גייסה אותי לפרויקט שלה ותוך כמה שבועות היתי בחיפה, מצלם שמונה ניצולי שואה בשחור לבן וצבע, שומע את הסיפורים שלהם, ומצלם מאלבום התמונות הפרטי שלהם תמונות מהחיים שבנו לעצמם, אחרי. מיד אחרי המפגש עם מרים ירדתי לגינת הטכניון, שם חיכתה לי כריסטינה עם כוס מיץ תפוזים סחוט טרי, לא יכולתי לעצור את עצמי והתייפחתי על כתפיה, מטולטל מעוצמת המפגש עם האישה המרשימה, מרים קרמין, שחצתה את כל הדרך כמעט מפולין לפלסטינה ברגל, ביערות. אחר כך בתערוכה בבית הכנסת הישן בברלין סיפרתי עשרות פעמים את הסיפור של מרים כחלק מפרפורמנס אחד גדול, שבו סופרו גם הסיפורים של לאה, אסתי, בנימין, זיגפריד, שרה ויוסף

היה גם מסע לזקסנהאוזן עם קבוצת תלמידים מתקדמים ברכבת, אחד מהם היה מוחמד, פלסטיני מרמאללה. הם היו כבר שוטפים בעברית אבל מה שאני זוכר זו שיחה מקוטעת שלנו בדרך חזרה בסבאהן שמנסה להבין ולחבר חלקים, שלי, שלהם. ופרויקט תאטרון של במאי ישראלי ושחקנית גרמניה, דור שלישי, שהיתי מעורב בו עמוק צילומית ורגשית, והמפגש עם אלבום התמונות של המשפחה של בן זוגי, בכפר הקטן, מנסים ביחד להבין אם הדוד הרע היה באמת בס.ס או בוורמאכט ומה עשה האבא של האבא בצבא ההונגרי. גם הוא לא דיבר

הלכנו שם, רוזה לידי מחזיקה קטורת מרווה בוערת ומהלכת יחפה, ליד תלים גדולים של אדמה חתומים באבנים ועליהם הכתובות: קבר של 500 איש, 1000 איש, 2000, מספר לא ידוע. אני שואל אותה איך היא מסוגלת ללכת יחפה כשאני מחשב מראש עם איזה נעליים אתהלך במקום כזה, היא אומרת שזה מקום קדוש, קדושת החיים. אנחנו מוסיפים לשמוע את מכונות הירייה של הצבא הגרמני, גם פה, במקום שבו עמד פעם המחנה, פה היו מגורי האסירים, מגורי שומרי הס.ס ובריכת השחיה שלהם, מחנה השבויים. אנחנו שומעים ציוצים של ציפורים שמשתלבים בהדי היריות

רוזה אומרת שאלה צריכות להיות ציפורים אמיצות במיוחד

The Trees of Bergen-Belsen

During our drive there, we stopped for a morning picnic and took out the sandwiches that I had made and the hard-boiled eggs that Rose cooked. We sat on a large wooden bench, all around us a rural landscape with red houses. Then, we heard bursts of machine gun fire. It turns out that we were on a side road near a large training area for the German army. From there to the camp, there were signs warning people not to stop at the side of the road and that photography was forbidden.

Since I came to Germany eight years ago, there have been quite a few moments when I have been faced with the past of this place, without effort or intention, reminding me of the place I chose to live in, and the weight that it carries.

I did not come here haunted by my grandparents’ stories about the Holocaust. I never dived deep into the black hole in my family history called “Grandpa Simcha’s Biography”, even though I wanted to for years, and very much want to, still, to clear some of the darkness there. During a residency in Berlin years ago, I made images inspired by a photo of him in a Soviet army uniform, and to this day I use a photo from his passport in several of my artworks. He died when I was a child, when we were in the United States. A few years later, my father died too. He probably never knew much because Grandpa Simcha did not talk about it. The children in the Kibbutz remember him as the lovable grandfather who handed out candy. On one of my recent visits to Israel, I went to Beit Hatfutsot with Dennis to search the database, but did not find out anything.

One of these encounters with the past happened during the first Hebrew lesson with a new student, a German director, in her beautiful apartment in Prenzlauer Berg, Berlin. She very quickly recruited me for her project and a few weeks later I was in Haifa, photographing seven Holocaust survivors in color and black & white, listening to their stories and taking photos of their private photo albums, of the lives they built afterwards. After the meeting with one survivor, Miriam Kremin, I went to the garden at the old Technion, where the director was waiting for me with a glass of freshly squeezed orange juice. I could not stop myself from crying on her shoulders, shaken by the intensity of the meeting with that impressive woman, who traveled almost the entire way from Poland to Palestine by foot in the woods. Later at the exhibition at the old synagogue in Berlin, I told Miriam’s story dozens of times as part of a big performance, in which the stories of Leah, Esti, Benjamin, Siegfried, Sarah and Joseph were also told.

There was also a train trip to Sachsenhausen with a group of my advanced Hebrew students. One of them was Muhammad, a Palestinian from Ramallah. They were already fluent in Hebrew but what I remember most is our broken conversation on the S-bahn back to the city, trying to understand and connect segments of our lives, mine and theirs. There was a theater project by an Israeli director and German actress, both third generation, in which I was deeply involved, also emotionally as the photographer. There was the encounter with my partner’s family photo album, in the small village, trying to figure out if the bad uncle was in the SS or Wehrmacht and what the father’s father did in the Hungarian military. He did not speak about it either.

We walked there. Rose, next to me, burned sage incense in her hands, and walking barefoot, next to large barrows of earth sealed with stones with these inscriptions: Tomb of 500 people, of 1000 people, of 2000, of unknown number… I ask her how she can walk barefoot when I had planned in advance the shoes that I would wear to walk in a place like this. She says it is a holy place, about the sanctity of life. We continue to hear the machine guns of the German army, also here, where the camp once stood. Here were the prisoner huts, the dwellings of the SS guards and their swimming pool, the prisoners of war camp. We hear the chirping of birds blend into the echoes of the gunshots.

Rosa says these birds must be especially brave ones.