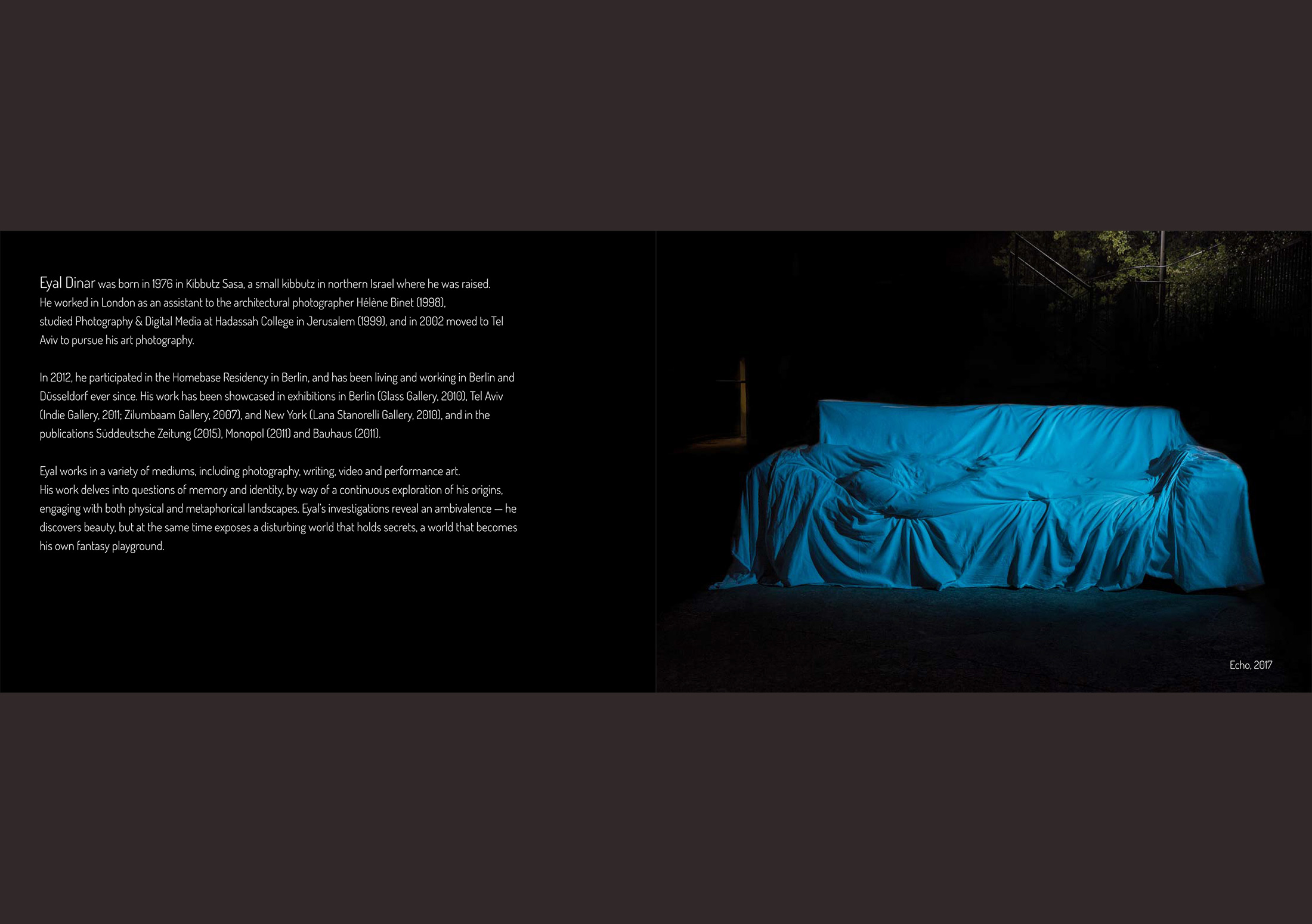

Six Swans

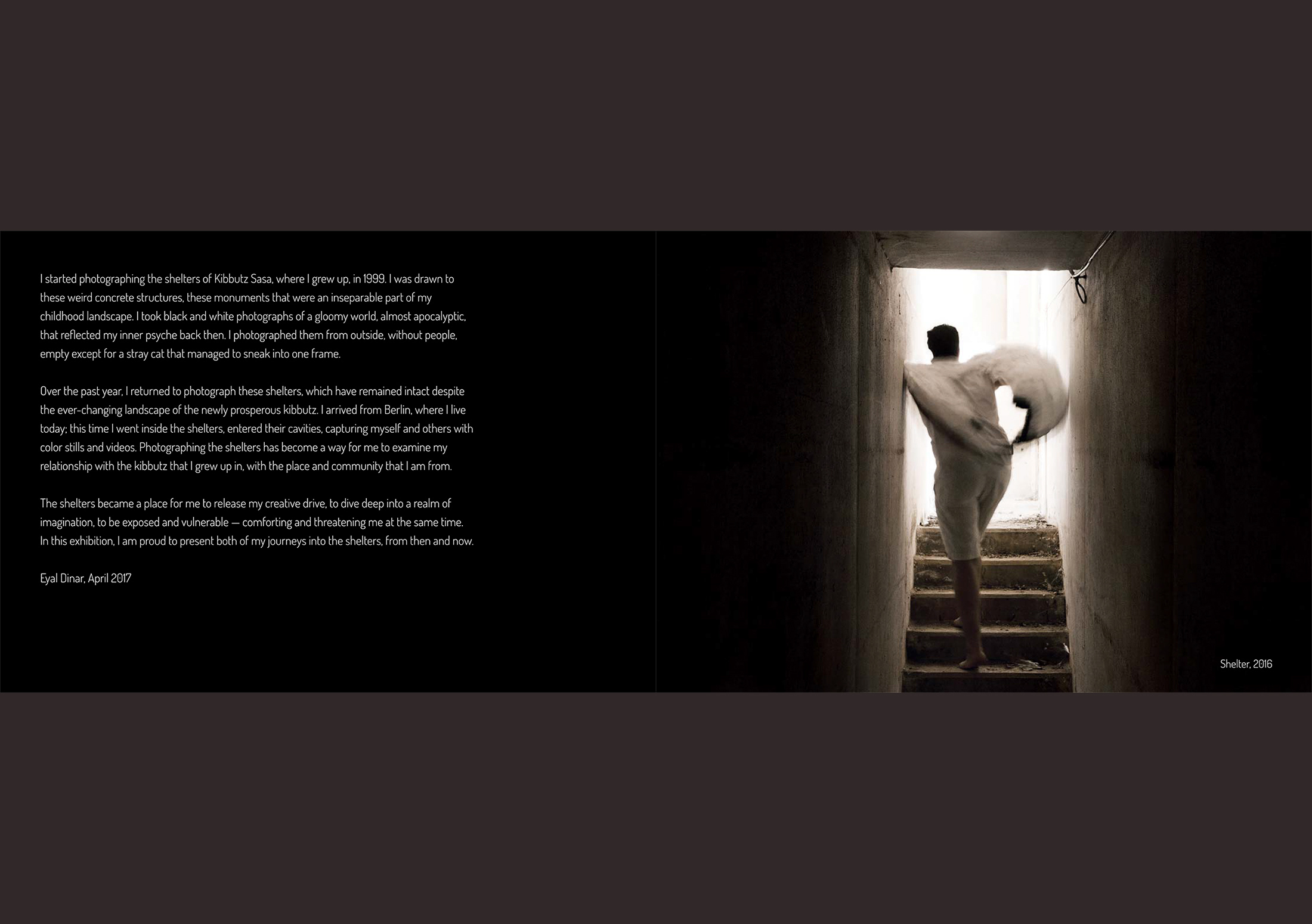

The project is an homage to the Brothers Grimm tale, “Six Swans,” which tells the story of six brothers who became swans after their wicked stepmother cast a spell on them. I focused on the metamorphosis theme in the story – the transformation of a human into a swan – and imagined it as a self-portrait, depicting the changeable situations of death and rebirth.

– Eyal Dinar, 2000

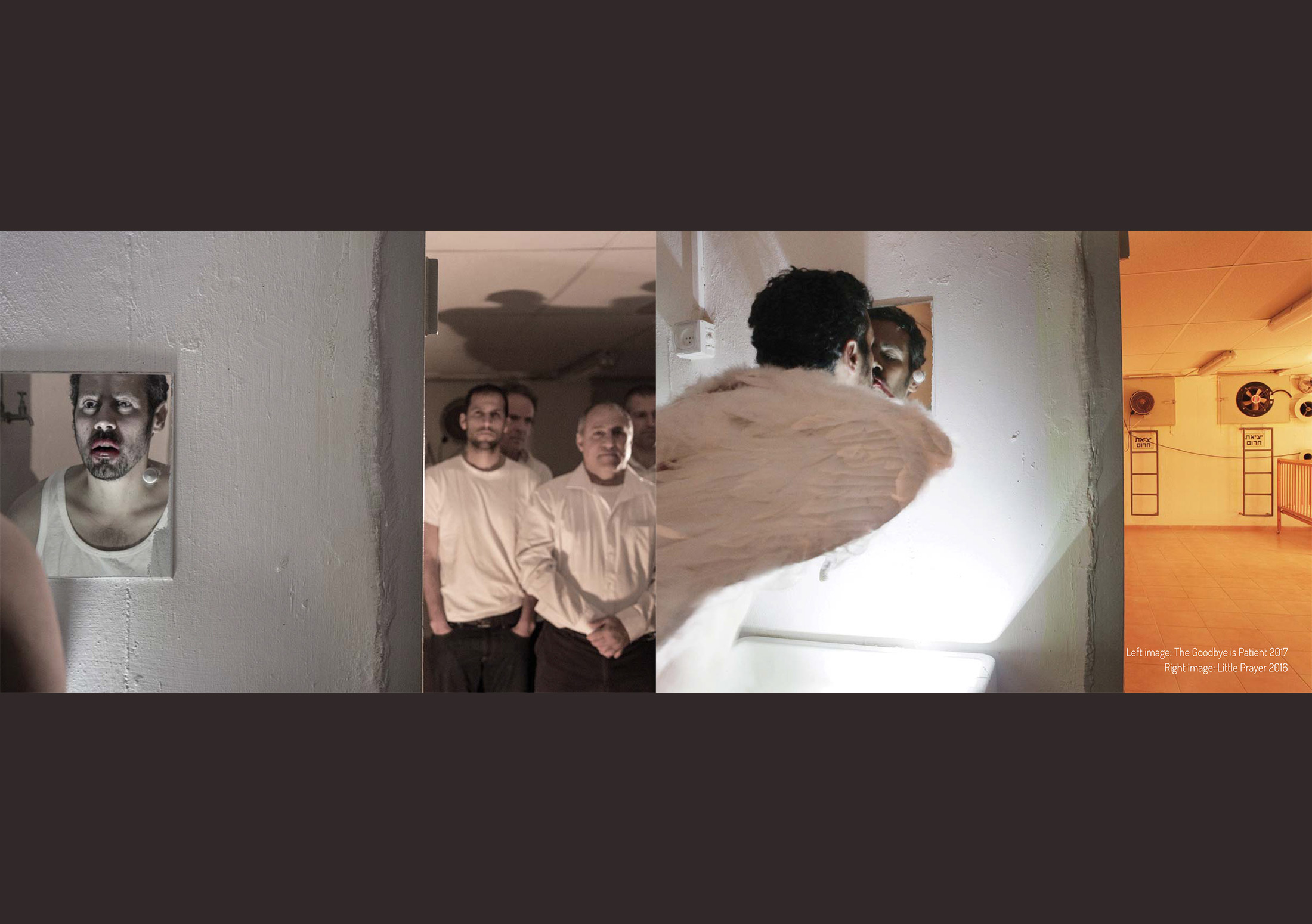

The depiction of the artist’s vibrating, agonizing body conjures the works of Francis Bacon, which portray the human body as a mass of matter distorted in pain. However, in contrast to Bacon’s work, which is immersed in despair and destruction, Dinar’s illustration of pain is more subtle and includes a glimmer of hope, as a phase before rebirth. The ritualistic context is reminiscent of the work of Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta, who in many of her works wished to directly unite with nature, through her body, to illustrate a process of inner reconciliation. However, compared to Mendieta, who depicts her rebirth with rigid and static body images of death, Dinar focuses on the intermediate phases of the metamorphosis that entail struggle and pain.

– Einat Ofir, Curator of contemporary art (text from exhibition at Galerie Glass, Berlin 2010)

Einat Ofir on Eyal Dinar’s series Six Swans

This series of photographs is based on the fairy tale “The Six Swans,” published by the Brothers Grimm, which tells the story of six brothers whose stepmother cast a spell on them and turned them into swans. Eyal Dinar takes this theme of metamorphosis and uses it as a metaphor for the human who wishes to recreate himself and rid himself of his burdensome distress. Unlike in the fairy tale, in which the metamorphosis is forced as a punishment, here it emanates from the depths of his soul.

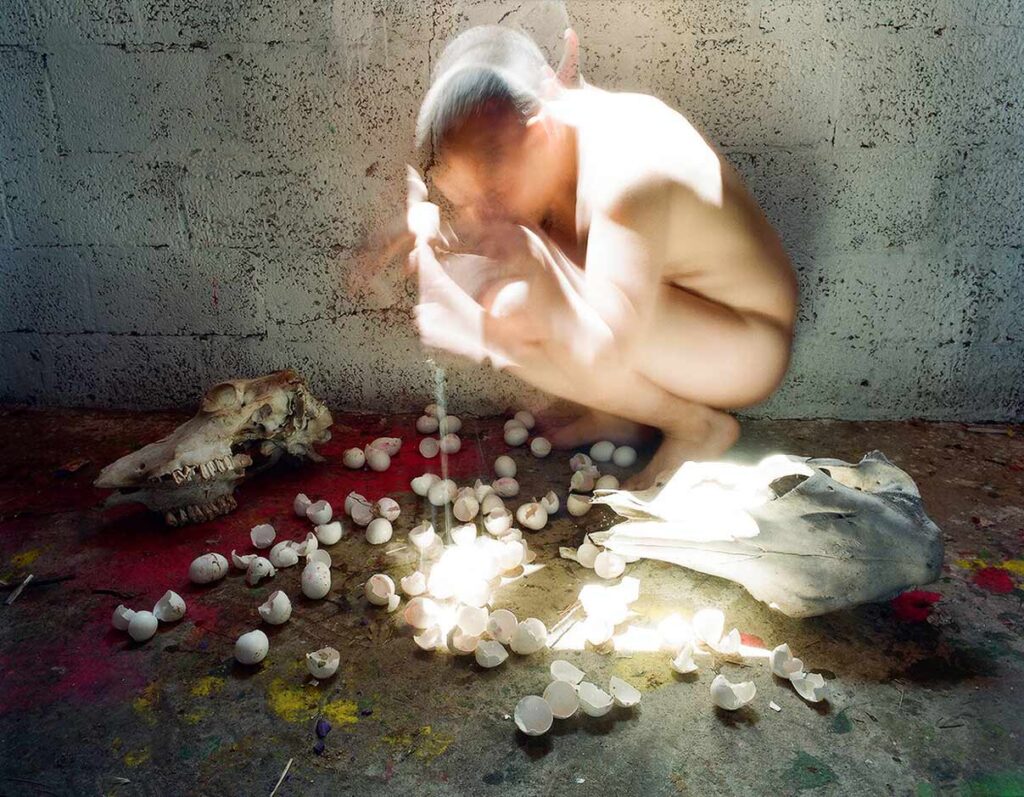

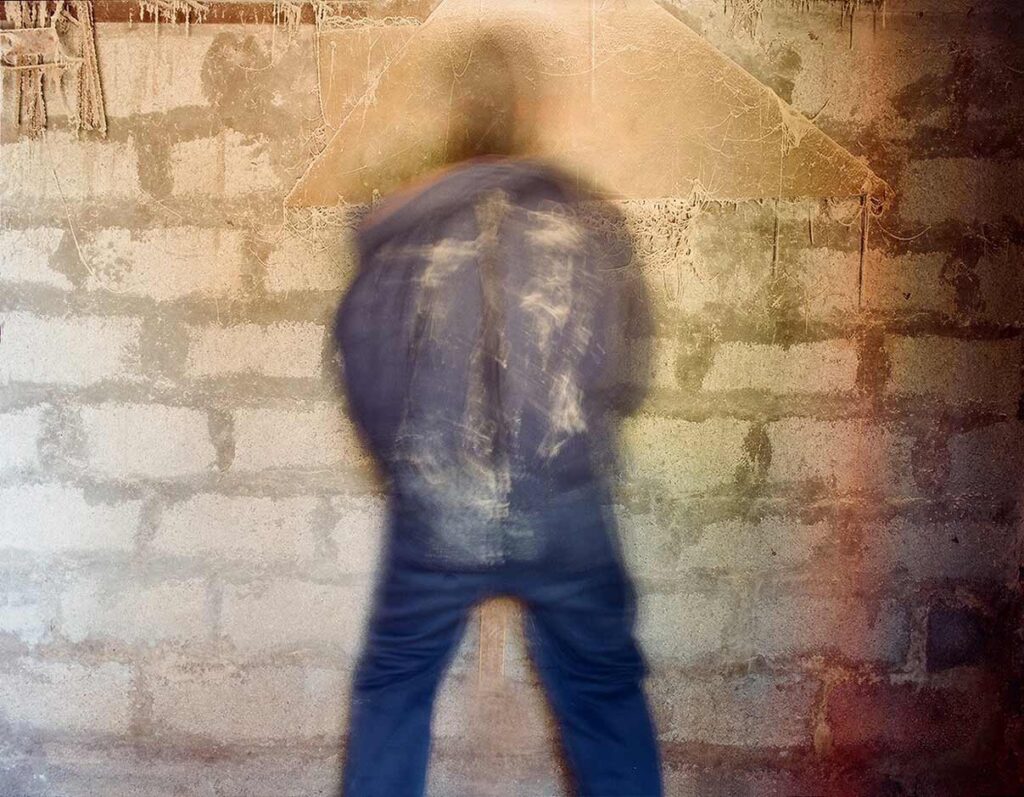

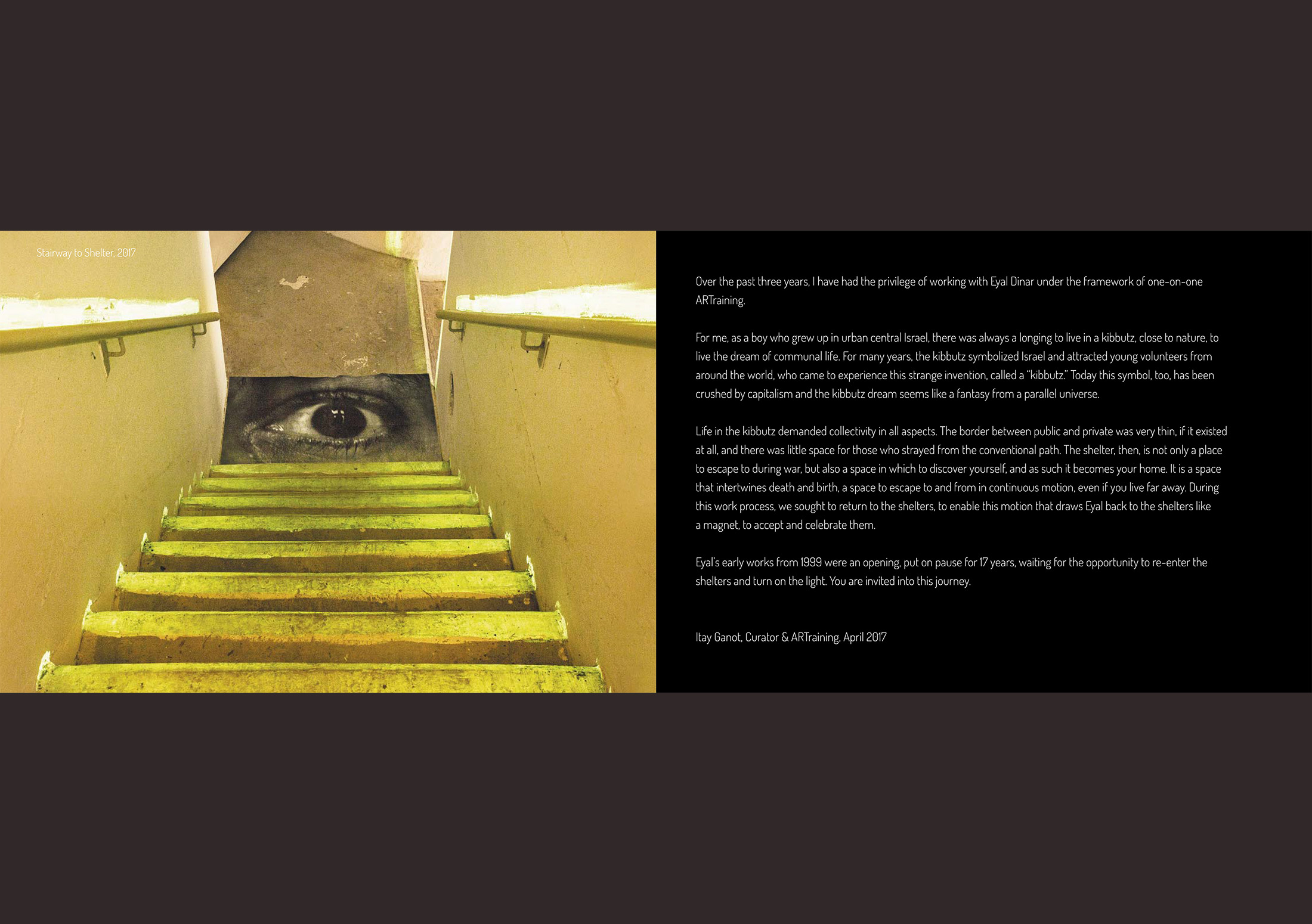

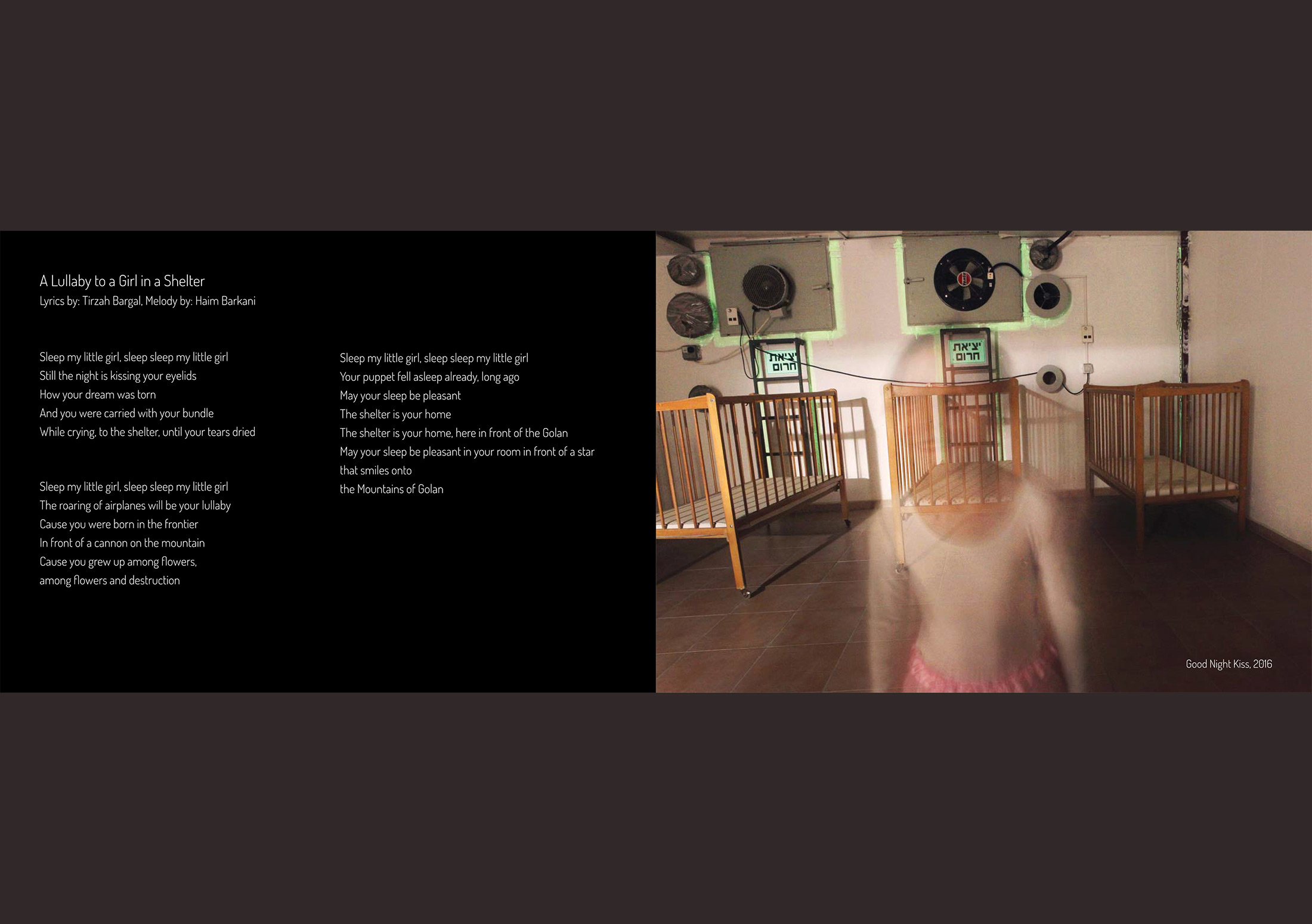

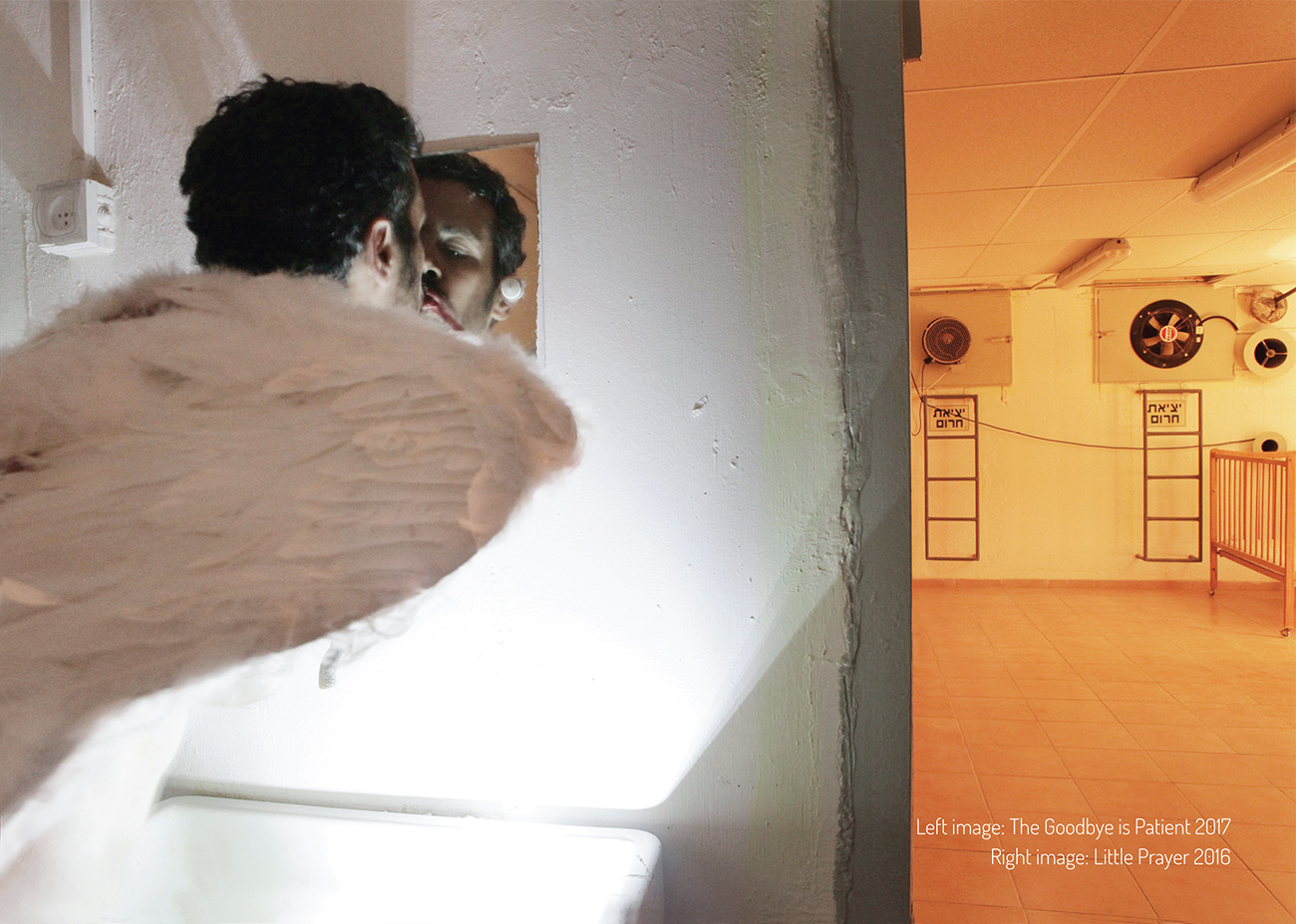

In this series the figure of the artist is seen as a blurred, vibrating object – in partial or full nudity. It seems that his body is convulsing and hurting, thus reflecting the painful phases of shedding his old identity. An affinity to the soil is present in the series and many photographs capture an abandoned thicket, which is a stage for seclusion. This context evokes the biblical verse, “Dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return.” However, Dinar presents death, the return to dust, as a metaphorical process, after which rebirth occurs.

The depictions of the transformation display a ritualistic aspect, in which the artist turns to higher powers and asks to destroy his old life in return for a new one. In one of the photographs, Dinar is seen squatting, his body gathered in a fetus position, which illustrates the process of rebirth. The artist is in an ancient cave, a kind of womb. Lit candles stand in the entrance, accentuating the ritualistic mood and charging it with the ancient symbolism of the transience of life.

In some of the photographs, Dinar stands close to a wall and turns his back to the viewer, or stands by a fence. In one of them he is seen from his back, squatting on the ground, gazing beyond the fence. His body leans toward the radiant sun and plants, expressing a plea for freedom. On the ground behind him is a pile of twigs in the shape of a bird’s nest. This nest is emphasized in another photograph, where the artist’s legs become a swan couple.

The depiction of the artist’s vibrating, agonizing body conjures the works of Francis Bacon, which portray the human body as a mass of matter distorted in pain. However, in contrast to Bacon’s work, which is immersed in despair and destruction, Dinar’s illustration of pain is more subtle and includes a glimmer of hope, as a phase before rebirth. The ritualistic context is reminiscent of the work of Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta, who in many of her works wished to directly unite with nature, through her body, to illustrate a process of inner reconciliation. However, compared to Mendieta, who depicts her rebirth with rigid and static body images of death, Dinar focuses on the intermediate phases of the metamorphosis that entail struggle and pain.

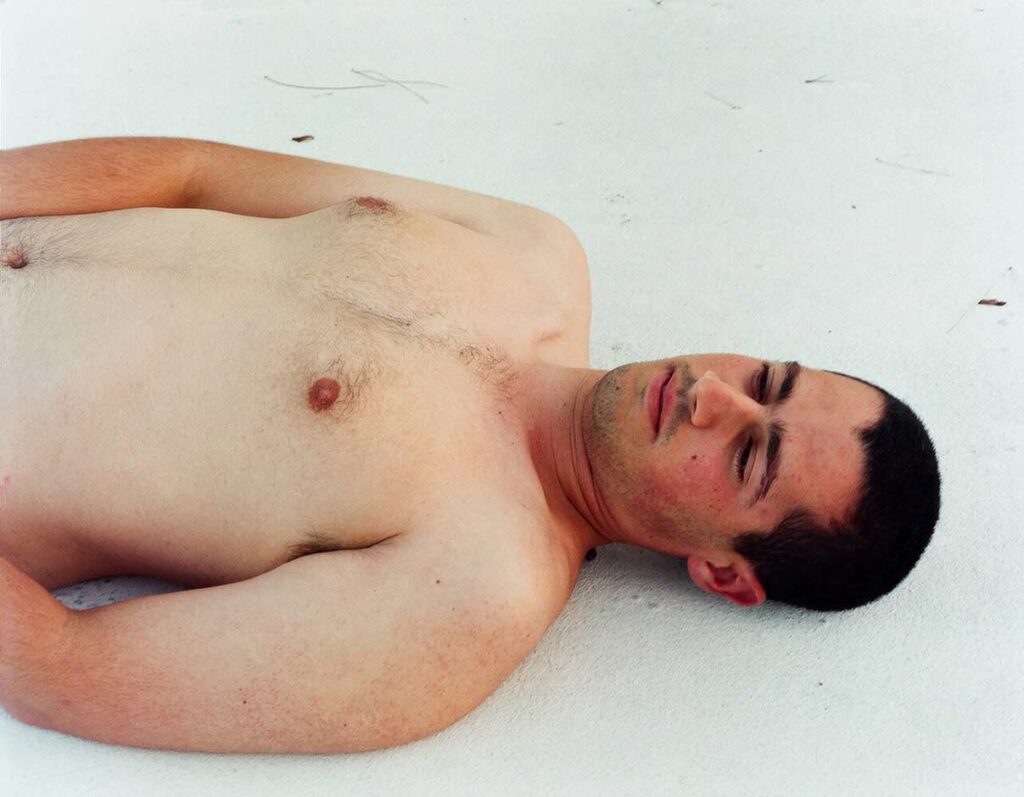

Dinar’s rebirth is presented in a triptych, which references the tradition of depicting the dead body of Jesus. Dinar, in full nude, lies completely serene. It seems that this is where the painful struggle ends. His location is an undefined, gleaming, illuminated space, and it seems that the light also bursts forth from his body. The dominant bright, pale light is reminiscent of the white of the swan. The metamorphosis has been completed.