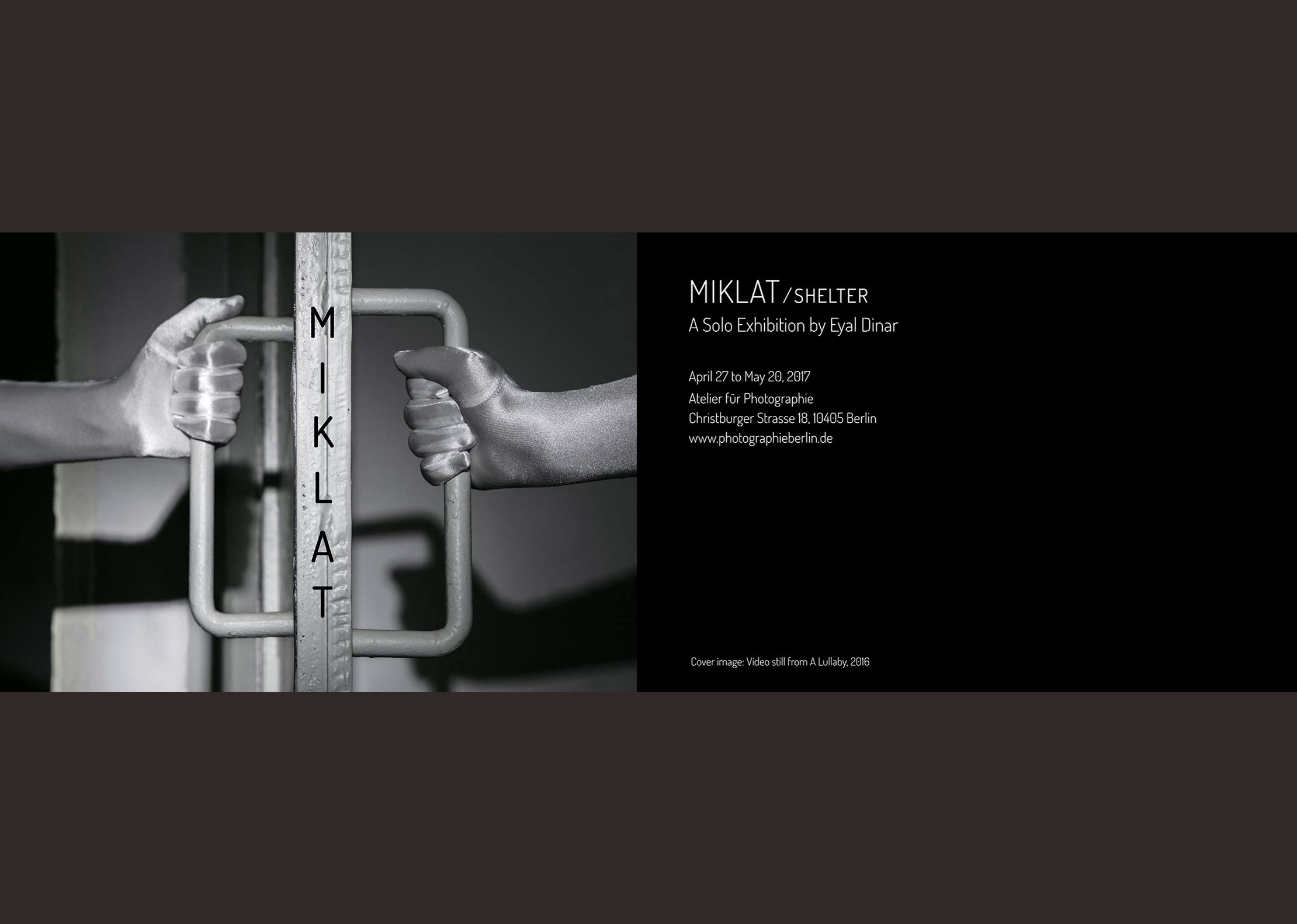

MIKLAT

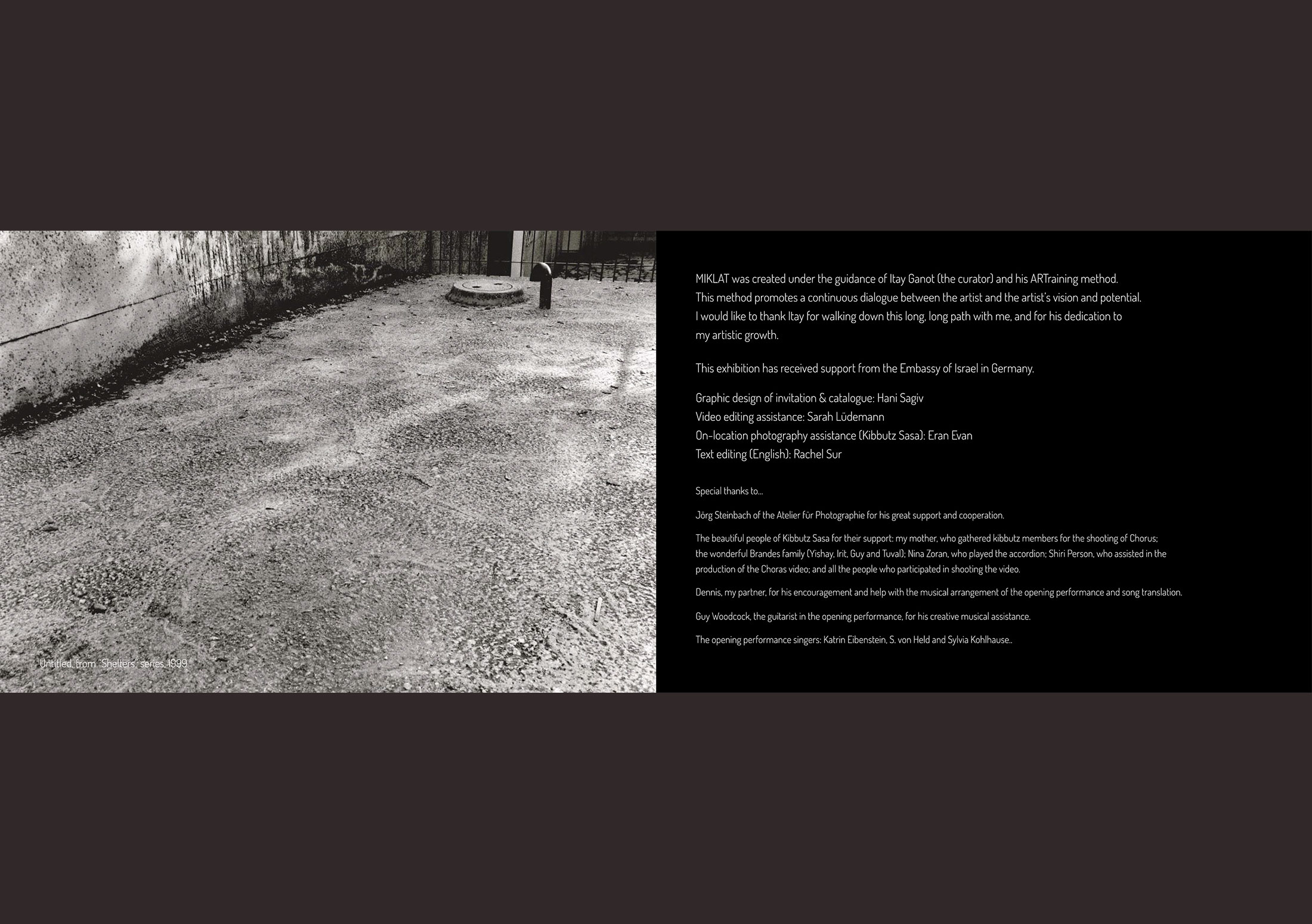

I started to photograph the bomb shelters of Kibbutz Sasa, where I grew up, in 1999. I was drawn to these weird concrete structures, these monuments that were an inseparable part of my childhood landscape, a place to protect us kids during wartime. I took black and white photographs of this gloomy – almost apocalyptic – world, which reflected my inner psyche back then. I photographed them from the outside, deserted except for a stray cat that managed to sneak into one frame.

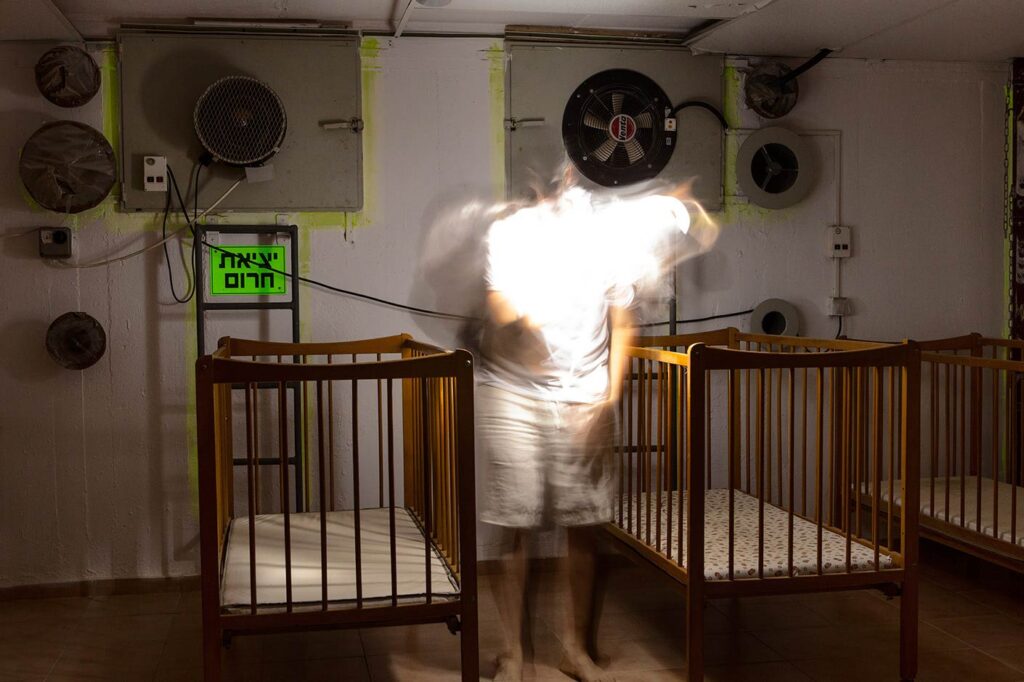

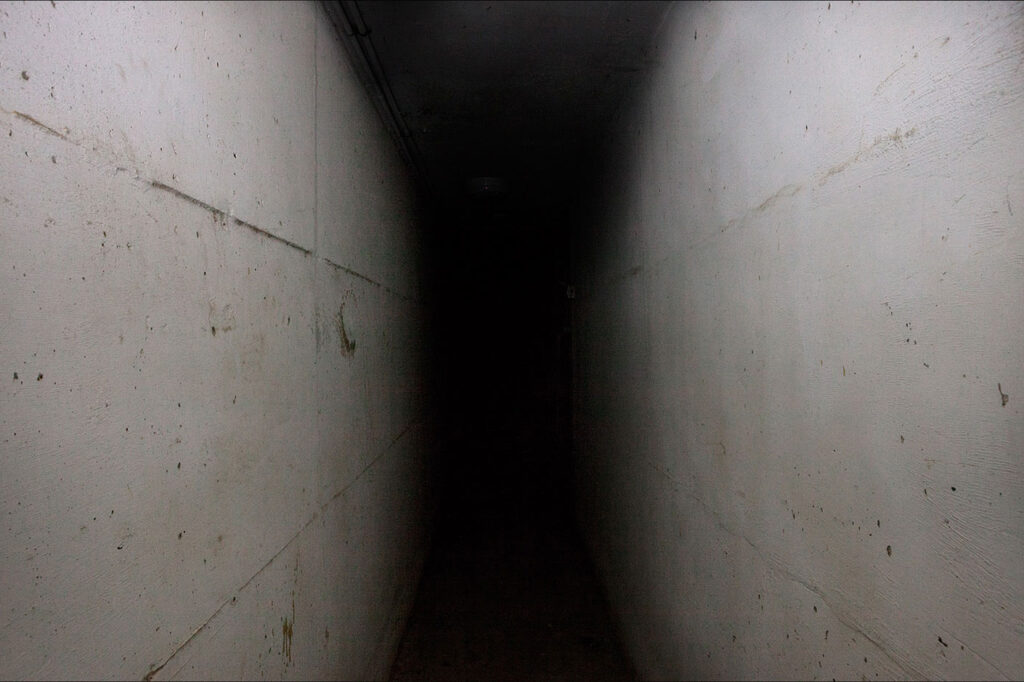

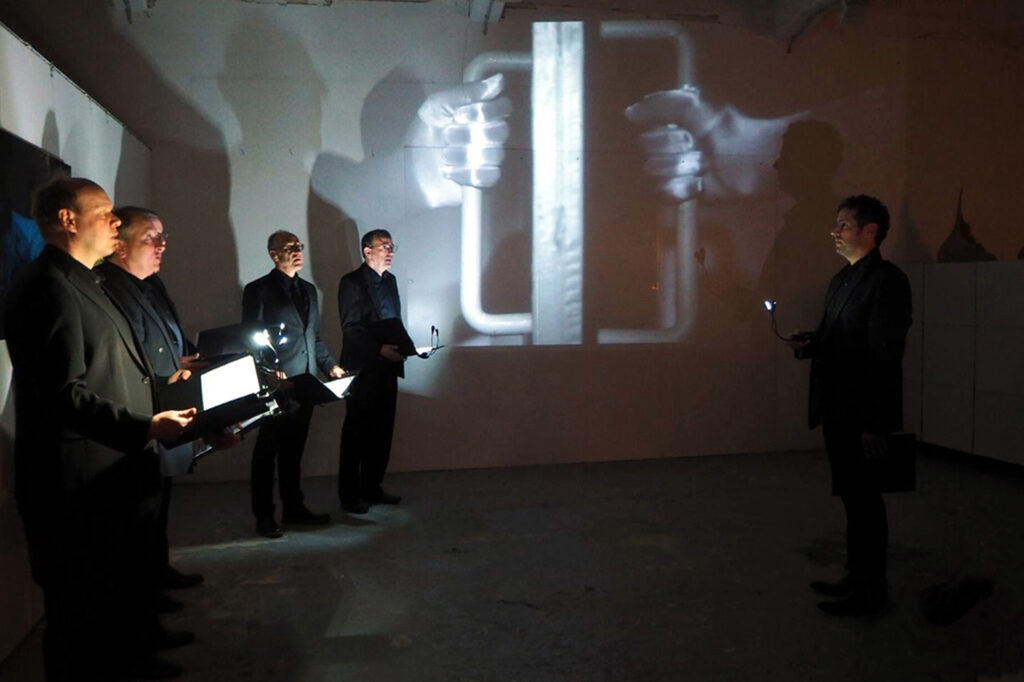

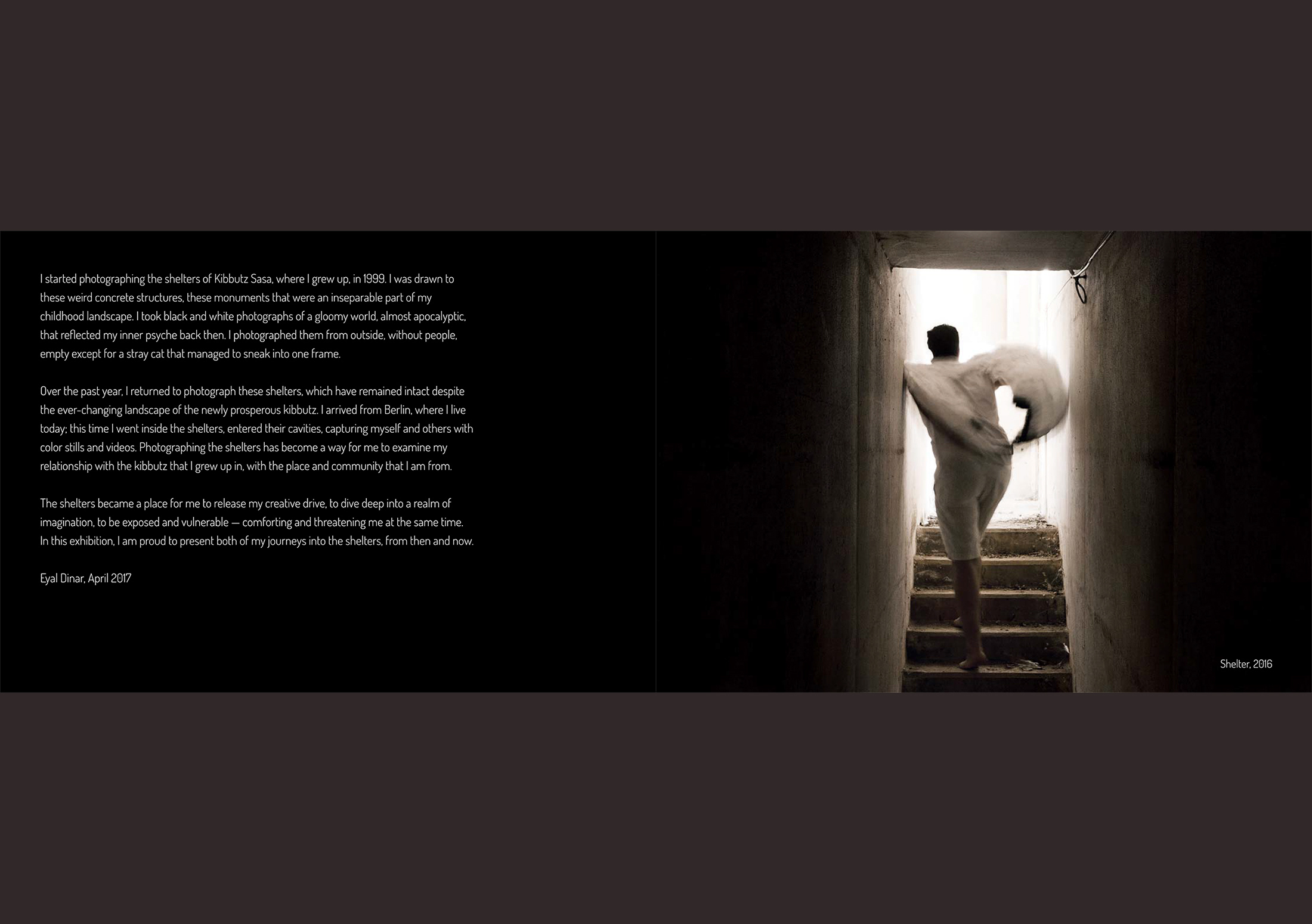

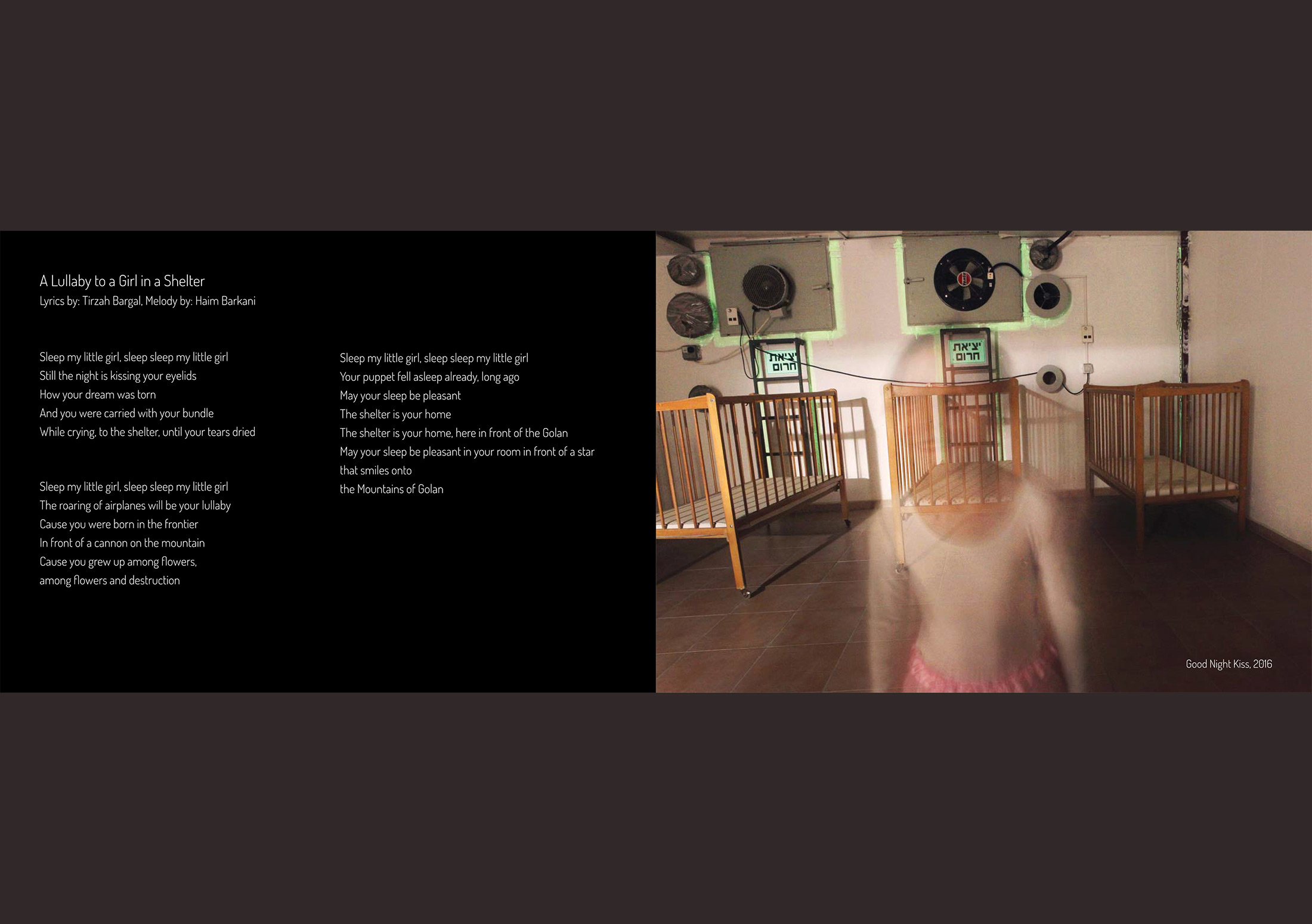

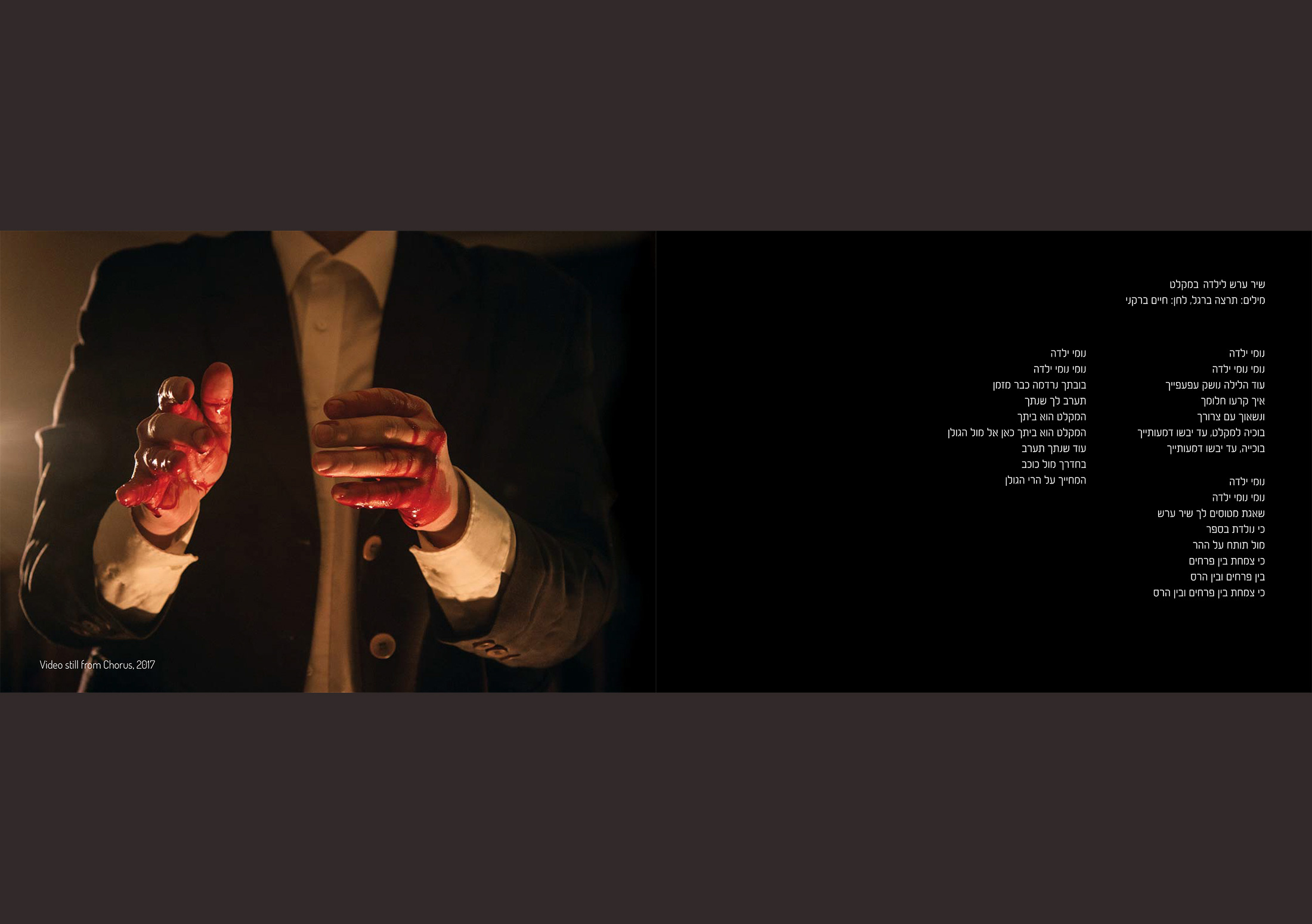

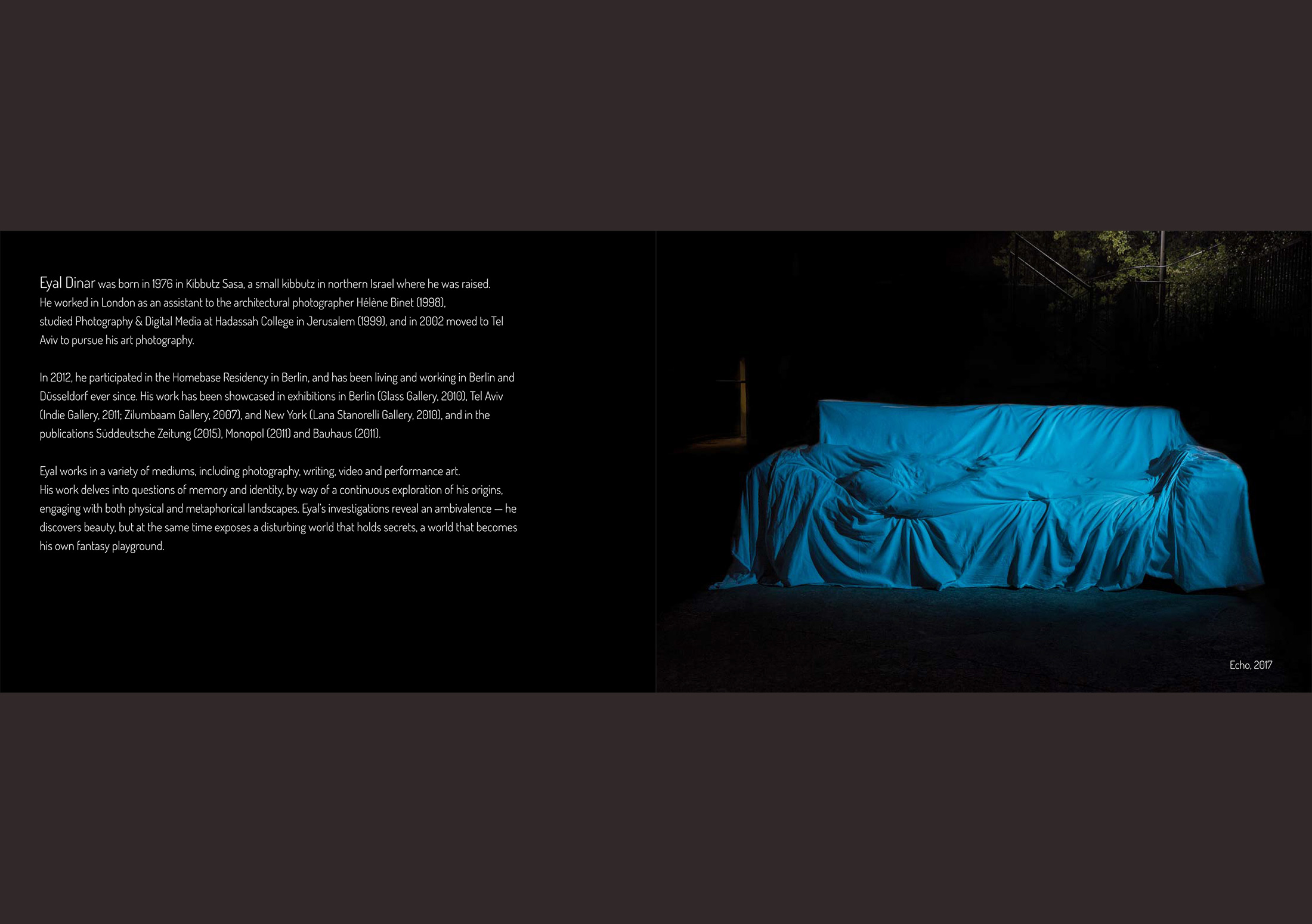

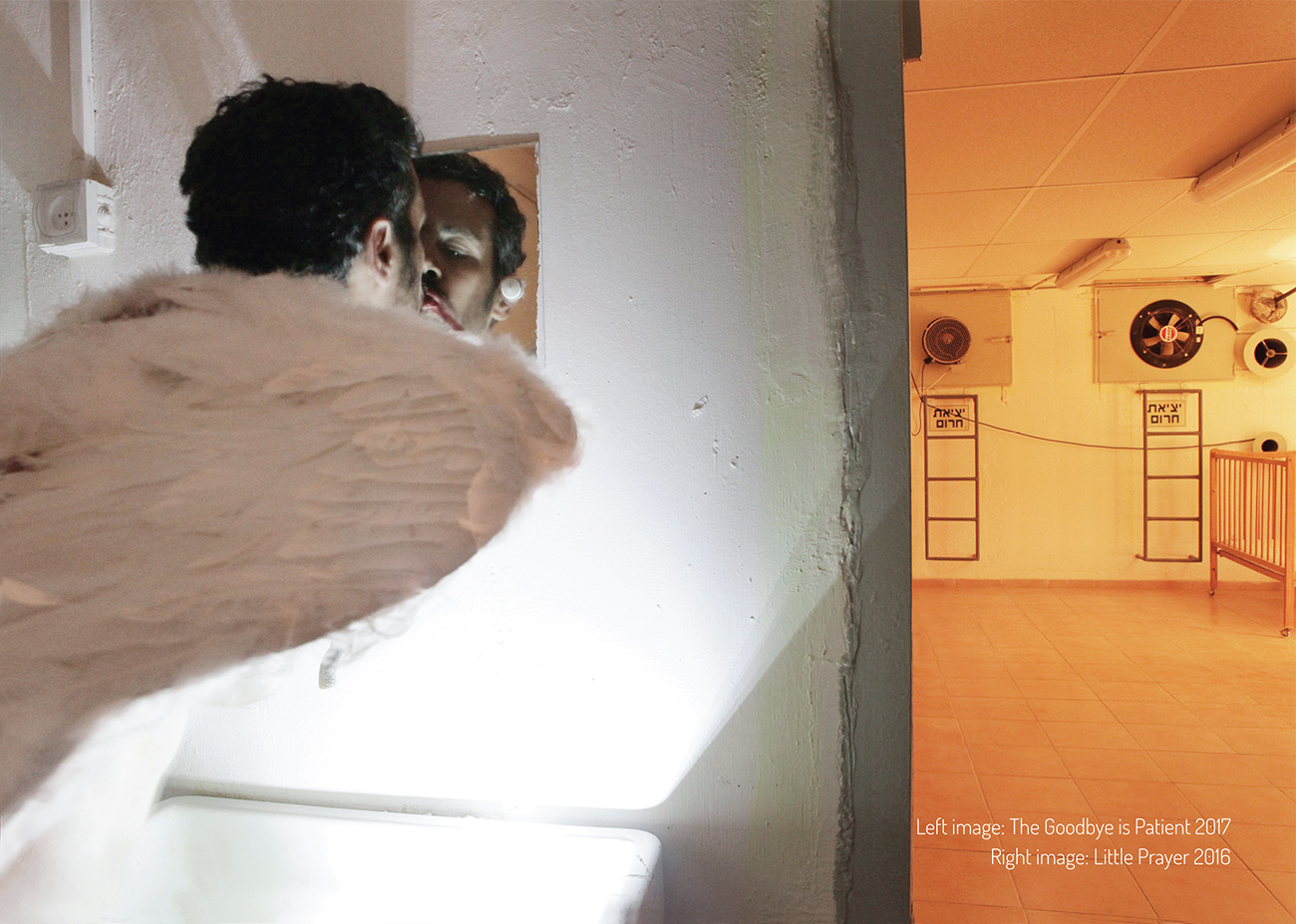

In 2015 I returned to these shelters, which remained intact despite the ever-changing landscape of the newly prosperous kibbutz. I arrived from Germany, where I live today. But this time, I went inside the shelters. I entered their cavities, capturing myself and others with color stills and videos. Photographing the shelters became a way for me to re-examine my relationship with the place and community that I am from. The shelters became a place for me to release my creative energy, to dive deep into the realm of imagination, to be both comforted and threatened, exposed and vulnerable, at the same time.

– Eyal Dinar, 2017

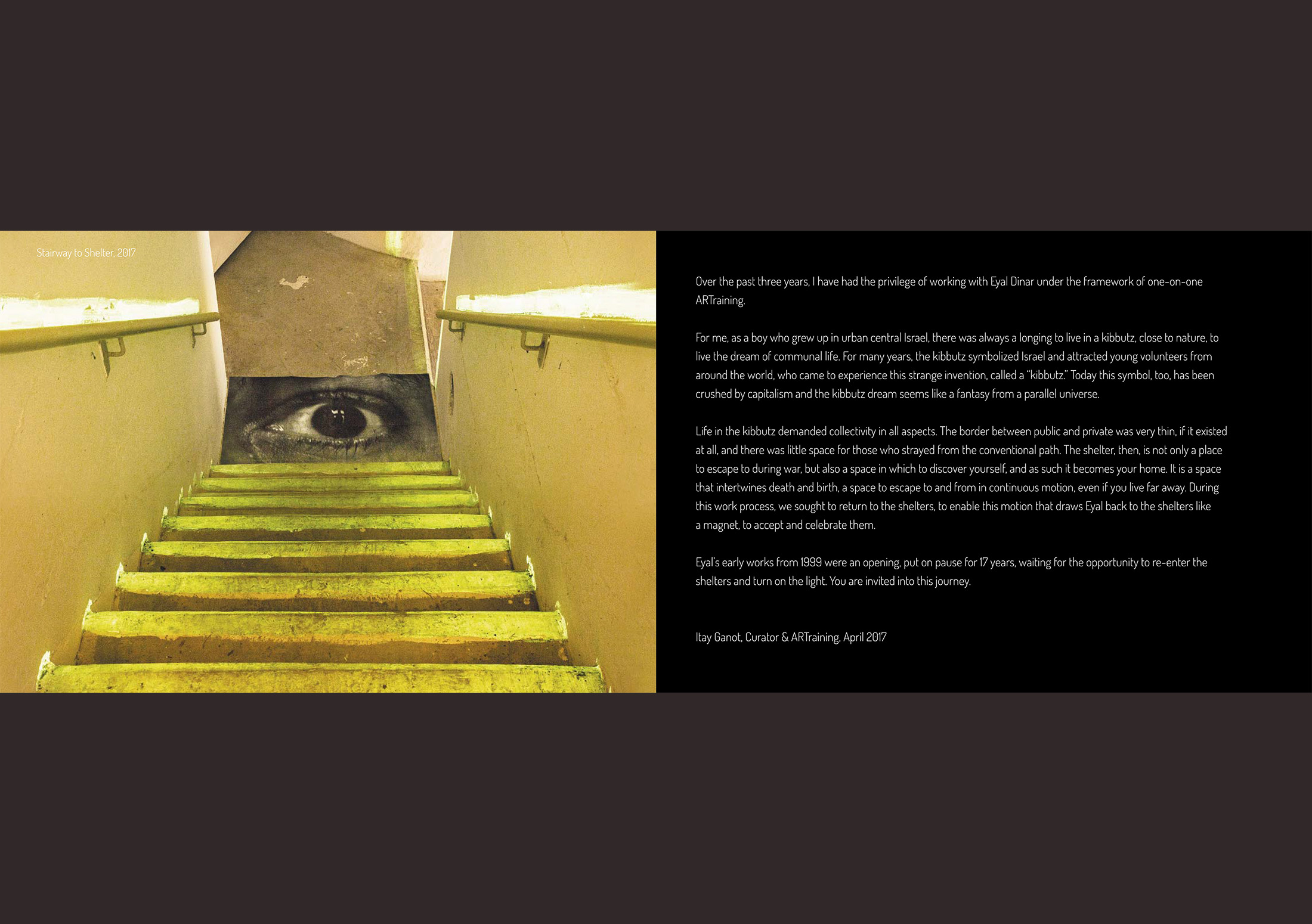

The shelter is a public space, a limited and congested underground cavity, bounded by iron and concrete walls. The shelter is a place where life is possible under the shadow of death. It triggers our memory of the unknown and the known. The shelter lacks the etiquette of hospitality. Sometimes we must escape to it, in the absence of choice, to find refuge from the horrors on earth.

Eyal chose to enter the shelter again, this time of his own free will.

The encounter with underground worlds alarms the soul. The ghosts of childhood memories, of ancient fears and struggles, dwell in these dark depths. But for Eyal, the unconscious is not just the seat of repressed trauma and archaic urges. The damp, dark shelter womb is also where an angel is born. Eyal asks us to ponder and probe: ‘Is the unconscious also the birthplace of the metaphysical?

– Dr. Ronen Pinkas (Modern Jewish Philosophy)